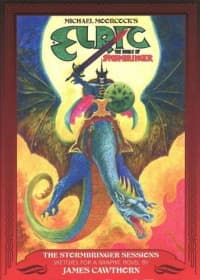

James Cawthorn: The Stormbringer Sessions: Sketches for a Graphic Novel compiled by John Davey

(Jayde Design/Savoy Books, 2021)

Reviewed by Andy Sawyer

It must be difficult for contemporary readers—even those who are fans of the work—to get their heads around what reading Michael Moorcock’s “Elric” series in the 1960s was like. The sudden flash of discovery in the mid-1960s was largely created by the fact that there really was comparatively little of that kind of fiction available, but it was quite clear to even the most naïve reader that Moorcock was picking up a genre and trying to pull it into the modern world. In 1965 J. G. Ballard—that’s J. G. Ballard, the darling of ‘experimental’ literary theorists—called Stormbringer “[a] work of powerful and sustained imagination which confirms Michael Moorcock’s position as the most important successor to Mervyn Peake and Wyndham Lewis… a world as fantastic as those of Bosch and Breughel…vast, tragic symbols… [a] metaphysical quest.” Not bad for a sword-and-sorcery novel. Moorcock’s ‘Eternal Champion’ series (of which the Elric sub-series is but a part) is perhaps too hastily constructed from its individual units to be entirely successful as epic, but if it has the feel of epic it’s in the doomed anti-hero Elric himself, who in these earlier works is like the heroes of Homer or the Norse sagas, self-aware enough to know that he is a tool of greater powers even as he shatters the world around him.

Associated with Moorcock throughout his career was the artist James Cawthorn, whose The Man and His Art, a memorial volume, was published by Jayde Design in 2018. Introducing this volume, John Davey said that Cawthorn was “born to draw Elric” and, though not discounting the splendid work of other artists, one can only agree. In 1976, Cawthorn illustrated Stormbringer, the climax of the Elric series, as a graphic novel for Savoy Books. It was, Davey writes, “somewhat more flawed than definitive”: as the publisher explained in The Man and His Art—a rushed job which the artist attempted to revisit but never felt able to bring to completion.

Which brings us to The Stormbringer Sessions—as Davey explains, it’s neither a finished graphic novel nor simply a collection of rough sketches. Found among Cawthorn’s archive were two boxes of roughs and photocopies comprising preliminary sketches for a twopart, 250-page new adaptation of Stormbringer. As the title suggests, the equivalent perhaps of a music demo by a songwriter at the height of his powers. A sword and sorcery Basement Tapes perhaps. It’s rough; sketchy in places, text crossed out and replaced, pages re-numbered, occasional mis-spellings and the odd note to self not to forget things. (“Remember the Horn of Fate,” reads one outside-the-panel note on page 127.)

But who is this massive production for? Certainly, readers of The Man and His Art, presumably mostly people who had been following Cawthorn throughout his career, will have no problems with The Stormbringer Sessions. Nor will those interested in seeing how the task of preparing a graphic novel of this scale is done. But this is more than a fannish tribute. Its unfinished nature is part of its fascination.

Cawthorn, whose roots were in fanzine art, was a master of that now almost forgotten medium whose strengths lie in immediacy and the transformation of a mental image through a stencil to the printed page. Comic book work demands similar intense visualisation, balancing the dynamic way stories are told through text and artwork, each reinforcing but also competing with the other. Seeing how the artist deals with the problems inherent in their chosen form is therefore always fascinating.

Davey tells us that the original artwork used a multiplicity of media (pencils, ball-points, felt-tips) in a multiplicity of colours. What we have here is a cleaned-up (monochrome) version, a rehearsal for a more detailed canvass in the way that the Great Masters of renaissance art prepared rehearsal “cartoons” for their works, or a film is storyboarded. In some panels, it can only be called “crude”. In others, the potential of what would be the finished pages is already present. But there are also moments of significant impact. Early in the story, a sorcerer delivers a cryptic message from a Chaos-demon to Elric. The ragged “hag” (not identified as man or woman in Moorcock’s text) is clearly a very minor sorcerer indeed, and explains that the demon was summoned to protect their “poor hovel” from the soldiers of Elric’s nemesis, the island of Pan Tang. Curious, Elric asks what the sorcerer gave in exchange for the power to summon a demon: “My soul, of course, Lord. But it was old and of little worth…”

Moorcock’s more complex take, with its sardonic “mock bows” and “Let me not keep you, my lord, for you have weightier matters on your mind” suggests an Elric simply puzzled by the motives of mere humans. But Cawthorn’s sketch of the muttered explanation to an Elric already galloping off on his horse shows the “wretch” staring at us with horror-filled eyes, wanting us, perhaps, to wonder how far Elric is avoiding engagement with ideas of justice and morality.

Much later, a double-page spread as the story reaches a series of climactic scenes shows two almost unnoticeable figures in a swirl of half seen shapes as “Blackness overcame the watchers as the landscape, and the whole terrestrial sphere, began to dissolve.” Here Cawthorn captures perfectly, without need for reworking, the tragic romanticism of Moorcock’s text. It needs little mental effort to imagine that, if Cawthorn had completed Stormbringer, it would have been a work which overshadowed practically all comic-book adaptations. In these pages, Elric still lives.

Review from BSFA Review 14 - Download your copy here.