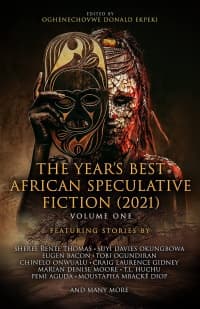

The Year’s Best African Speculative Fiction Volume One Ed. O.D. Ekpeki

(Jembifola, 2021)

Reviewed by Fiona Moore

African science fiction, fantasy and related genres are currently experiencing a long-overdue rise in visibility to global audiences. This is reflected in the publication of the first Year’s Best collection from the continent and its diaspora. The contents of this volume are of sufficiently high quality and breadth to encourage one to hope that this will be the first of many.

Less than twenty years ago, it was possible to publish a collection of “African” SFF which consisted almost entirely of White Americans writing about Africa, with one token, and also White, South African writer. Fortunately, the field has come a long way since the publication of Future Earths: Under African Skies (Dozois and Resnik [eds] 1993), and most habitual SF readers can at the very least name several writers from the African diaspora if not the continent itself. This volume is edited by Oghenechovwe Donald Ekpeki, an award-winning Nigerian SFF writer whose past credits, as Ekpeki Oghenechovwe Donald, include co-editorship of last year’s volume Dominion (Knight and Donald, 2020), which brought a lot of new and established-but-less-known African and diaspora authors to the attention of the wider world, including several now featured in this volume.

Two of my favourite stories from the Dominion anthology are featured, “Red Bati” by Dilman Dila and the Theodore Sturgeon Award-shortlisted “A Mastery of German” by Marian Denise Moore. I was also pleased to see “Scar Tissue” by Tobias S. Buckell, a touching and believable story about a working-class man who acts as parent to a nascent artificial intelligence, which deserves to get a wide readership. Other standouts include “Things Boys Do” by Pemi Aguda, a clever twist on the trope of horrific children, which is short but packs a huge emotional punch. “The Thoughtbox” by Tlotlo Tsamaase is less accessible, but weaves in a narrative about gaslighting and spousal abuse with cyberpunk staples such as stolen identity and questioning personhood. “The Future in Saltwater”, a climate-change fantasy by Tamara Jerée, had some clever worldbuilding that left me wanting more: it features a girl sent on a quest by a god, but the deity in this case is an octopod being which physically bonds with its worshipper. “Dessicant”, by Craig Laurance Gidney, is an original story using vampire tropes as a way of exploring sick-building syndrome and neglected estates, with a courageous trans-feminine protagonist. “A Curse at Midnight”, by Moustapha Mbacké Drop, takes the familiar fantasy trope of the “rational” young woman who comes to discover her family’s magic and abandon her skepticism, and roots specifically in Senegalese/Muslim beliefs and subtexts about colonialism.

As the above should make clear, the stories span all genres of SFF, from The Expanse-style hard SF, to Weird fiction, via high fantasy, horror, climate fiction, and cyberpunk. Several of the fantasy stories tend towards the Weird, which may reflect editorial preference (the same was also true of Dominion) or may indicate more general trends in African and diaspora fantasy (see, for instance, the rise in responses to Lovecraft by Black authors such as P. Djèlí Clark and Victor Lavalle, and the surreal fiction of Rivers Solomon). Themes of parenthood, family and relationships with the past also emerge through many of the stories, from both straight and queer perspectives.

The authors represented are also a suitable mixture in terms of their global recognition. A few well-known names are included, for instance Craig Laurance Gidney, Suyi Davies Okungbowa, and Sheree Renee Thomas, with rising star Eugen Bacon contributing the colonial satire “Baba Klep”. Other writers, such as Dilman Dila and T.L. Huchu, have a strong track record but are perhaps less recognisable by those not familiar with the African writing scene, and some, like Shingai Njeri Kagunda, are closer to the start of their careers. All the writers make strong contributions, and one definite contribution of this volume is to bring the work of the less familiar writers to greater global attention.

The distribution of nationalities is, however, perhaps more controversial from a literary point of view. Despite the volume’s mandate to present African SFF, a rough survey of the authors’ biographies shows a clear dominance by American writers (albeit from the African diaspora), outnumbering Nigerians, the next largest category, by two to one. To make up for this dominance, there is a broad spread otherwise, with writing by Ugandans, Kenyans, a Zimbabwean, Senegalese and Motswana, and in the diaspora outside the USA we have representation from an Australian, a Caribbean and a Canadian author.

I have mixed feelings about this distribution, as it is understandable given the current nature of the literary world in general and SFF publishing in particular. It’s also certainly true that African-American writers are an underrepresented group who deserve much wider promotion than they have historically received. However, it’s also worth noting that this would be unlikely to happen in other cases (the Year’s Best British SF, for instance, only includes British diaspora writers if they also happen to be resident in, or citizens of, the British Isles). It is probable that, as SFF from the African continent itself gets more and more established and more widespread recognition, this situation will be self-correcting.

The Year’s Best African Speculative Fiction Volume One is a good general representation of the state of SFF in Africa and the diaspora, worth recommending both to people familiar with African and diaspora writing, and to those who are hoping for an introduction to its current trends and concerns. The book is well put together, with a diverse range of high-quality stories by both well-known and less-familiar writers. One can certainly hope Volume Two continues this trend.

Review from BSFA Review 16 - Download your copy here.