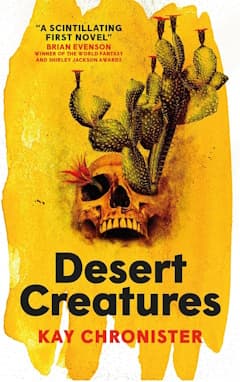

Desert Creatures by Kay Chronister

(Titan, 2023)

Reviewed by Niall Harrison

It’s a little unfortunate for Kay Chronister that in between last year’s US edition of Desert Creatures and this year’s UK edition a lot of people will have watched the TV adaptation of The Last of Us, and will as a result have in their minds vivid imagery of a father-daughter team, traversing wilderness and confronted with human bodies that have been transformed by other biology, to compare with this:

They came suddenly to a forest of cactus arms wrapped around each other: thin and sinewy and curling from the trunk of a limbless human form in a dust-crusted denim shirt. Rising from the arms were red flowers with wide yellow stamens […] Even from a distance the smell of the vegetation was bright, rusty, palpable […]

“Never seen one still rooted,” he murmured.

To be clear I don’t think Chronister’s writing is bad, either in this specific instance—I’m a big fan of the efficient unpleasantness of that “rusty” smell—or in general. Desert Creatures has a terse brevity that suits its hollowed-out world, where there isn’t much time to spend on luxuries. We never get much more explanation for transformations like the one above than, “He died and the desert got inside him”; locations are charcoal-sketched more than oil-painted; and, with one notable exception that I’ll come to below, characters are icons and roles more than they are people. All of this is clearly strategic, and all of it is suitable for a story that aspires, as this one does, to the pared-back quality of myth. But it also draws on familiarity in a way that leaves the novel vulnerable to a sort of imaginative gazumping that, particularly but not only for those reading it in late 2023, may make the opening pages feel more second-hand than they are.

Because although Chronister’s “stuffed men” are not the same as the Infected they sometimes play the same role, and although Xavier and Magdala are not Joel and Ellie, they do initially appear to have something of the same dynamic, and the first community they encounter has a barbed-wire perimeter and a deep mistrust of strangers. And while over the course of the first third of the novel, other reference points come to mind—for me the novel’s indeterminate but not-too-far-off version of the US South-West has a similar blasted quality to the future of Paolo Bacigalupi’s The Water Knife (2015); the pervasive, oppressive sense of threat reminded me of Yuri Herrera’s novellas set in the US/Mexico borderlands; while Magala herself, who pretty quickly becomes the single protagonist of the story, is perhaps going to grow up into the sort of hardened desert survivor that populates Kameron Hurley’s Bel Dame Apocrypha—I still found myself waiting for Desert Creatures to fully snap into focus. I had to wait for the novel's middle third.

After an opening movement that serves to gradually strip everything away from Magdala, while introducing us to a set of locations and customs that set the thematic parameters of the story—unforgiving patriarchy; true and fraudulent faith; the frailty and possibility of human bodies; a Canterbury Tales of origin stories for how the world got this way—we abruptly switch from third-person present-tense narration to first-person past-tense. For the second hundred pages we read the testimony of Arturo, a man who grew up in Holy Las Vegas, with its panoply of saints and relics, became a priest in the church, and was subsequently exiled for heresy. He encounters—is captured by—Magdala, who is desperate to leave the orphanage she has fetched up in and travel to Las Vegas. She uses Arturo, with some ruthlessness, to achieve that goal, but through his wearily lived-in narration we can more clearly see her as the catalyst she is. “The girl never spoke to me before the day she held me at gunpoint”, Arturo recalls, but in her captivity, “again and again she tested my indifference to my earthly existence, and again and again I clung miserably to life, making whatever compromises were demanded of me.” As one character later (somewhat unnecessarily) observes, this is a world in which dead things aren’t always dead, and living things aren’t always alive, and some things move back and forth between those categories.

Flashbacks to Arturo’s life before exile depict a variety of hardships and unpleasantnesses, but also his talent for healing—one of a number of apparent miracles dotted throughout the book, which may or may not be connected to the wider transformation of the desert. But it is a poorly understood, temperamental gift, flowing through Arturo when it chooses rather than called by him. Chronister’s depiction of the involuntary compassion that overtakes Arturo in such moments, “so stubborn and unbegrudging that I would have sat for a hundred years with [a patient]”, is for me the most powerful emotional note in the novel, and when the final third moves back to third-person narration focused on Magdala, the memory of Arturo’s experience, of what being a saint and a miracle-worker in this world actually means, adds both a resonant melancholy and a tentative sense of hope.

The world has by this point become even more exhausted, the grip of Las Vegas that much more severe: “everything’s been emptied out”, one character notes. But I never believed that the novel would leave Magdala trapped in an ending with no possibility of renewal, so the question that loomed in the final pages was not so much whether but how that possibility would be presented: how expansive it would be, and whether it would bloom beyond a lingering sense of familiarity into something new. I don’t think it did. Perhaps that’s on me. But I’m not sad to have travelled with Arturo.

Review from BSFA Review 22 - Download your copy here.